Sad. I'm tired leaving behind the unfinished projects.

I have to go back to the original, the novel. In Russian. Camus didn't do it right...

5.12.03 I am not ready.

I have to do it smart way, or my summer is gone; another original adaptation/translation? ...

What is wrong with the Camus' play? It has the NOVEL structure, it's not DRAMA for stage!

... This is to work on in 2004. After-show page.

One thing to save -- Dostoevsky's humor. In Camus' adaptation it's missing...

"The second half of a man's life is made up of nothing but the habits he has acquired during the first half." Fyodor Dostoevsky

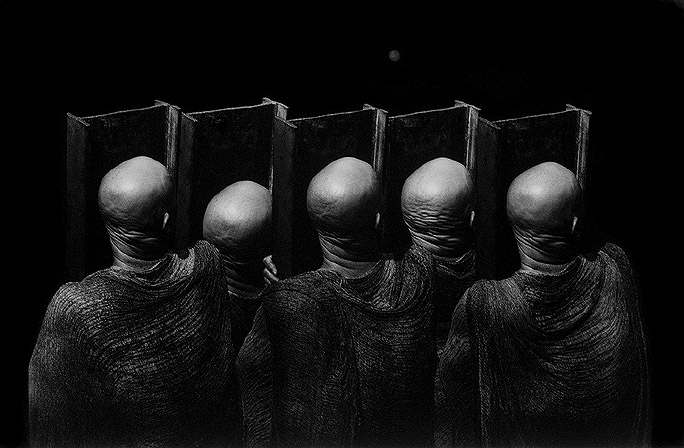

I see where the problems are -- Would they (actors, public) accept that the terror is in us? Dostoevsky wrote about himself, about Russia and Russians. He went to the heart of this existential basis of life and living. America today lives big lie; we call it "War on Terror" -- what a nonsense!

"Demons": Inspired by the true story of a political murder that horrified Russia in 1869, Fyodor Dostoevsky concieved Demons as a "novel-pamphlet" in which he would say everything about the plague of materialist ideology that he saw infecting his native land. What he emerged with in 1872 was at once his darkest novel until The Brothers Karmazov and his most ferociously funny. For alongside its relentlessly escalating plot of conspiracy and assassination, Demons (which earlier translators eroneously titled The Possessed) is a blistering comedy of ideas run amok. And, like all of Dostoevsky's novels, it is also a riot of literary voices, whose profusion, energy, and variety are rendered wonderfully in this new English version by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, winners of the PEN Book-of-the-month Club Translation Prize. (buy and read)

“The Possessed” Scene List by Character

An (X) next to a character’s name denotes that character’s death in that scene.

1 - Varvara’s: Varvara, Stepan, Stavrogin, Shatov, Dasha, Gagnov, Liputin, Shigalov, Virginsky

2 - Kirilov and Shatov’s dwelling: Maurice, Kirilov

3 - Kirilov and Shatov’s dwelling: Maria, Shatov, The Captain

4 - Varvara’s: Stepan, Shatov, Varvara, Lisa, Maria, The Captain, Peter, Stavrogin, Maurice, Dasha

5 - Varvara’s: Stavrogin, Peter, Stepan

6 - Rooming house: Stavrogin, Kirilov, Shatov

7 - Bridge: Stavrogin, Fedka

8 - The Captain and Maria’s dwelling: The Captain, Maria, Stavrogin

9 - The street: Stavrogin, Fedka

10 - The forest: Kirilov, Maurice, Stavrogin, Gaganov

11 - Varvara’s: Dasha, Stavrogin, Peter

12 - Rooming house: Kirilov, Shatov, Peter, Liputin, Virginsky, Shigalov, Lyamshin, The Seminarian, Stavrogin

13 - The street à Varvara’s: Stavrogin, Peter, Dasha

14 - Tihon’s cell - Stavrogin, Tihon(voice-over)

15 - Varvara’s: Stavrogin, Peter, Stepan, Varvara, Lisa, Maurice

15A - The Captain and Maria’s dwelling: The Captain(X), Maria(X), Fedka

16 - Country house: Stavrogin, Lisa, Peter

17 - The street: Lisa(X), Maurice(X), Stepan

18 - Shatov’s room: Mary, Shatov, Kirilov, Lyamshin

19 - The forest: Peter, Virginsky, Liputin, Shigalov, Shatov(X)

20 - The street: Peter, Fedka

21 - Rooming house: Kirilov, Peter, Mary(X) (Also, Mary’s newborn(X))

22 - Varvara’s: Varvara, Stepan(X), Dasha, Stavrogin(X)

An English translation of Ludmila Saraskina’s

The Possessed ¾ the novel of warning

by Yelena Matusevich

Translator’s introduction

From the moment I read The Possessed ¾ the novel of warning in 1994, I had dreamed, in spite of the length and especially Saraskina’s very difficult, almost untranslatable language (sometimes the language of the translation is a little odd but it is a trait which it shares with the original), to translate this book. I was impressed by the consistency and quality of her arguments, by the amazingly broad approach combined with deep reflections, by Saraskina’s encyclopedic erudition, and her real passion for Dostoevsky. But most of all, I was impressed and moved by the courage that she shows particularly in the last chapters of the book, the courage that very few Russians have ¾ to face their “revolutionary” past.

Indeed, Saraskina’s book responds to the growing necessity to understand how, why, and when Russia became the country of the possessed, the country where horror, humiliation, betrayal, and denunciation became every day business.

Ludmila Saraskina is a very well known critic in Russia and Europe, especially in Germany. In the preface to her book The Possessed ¾ the novel of warning, she declares that the study of Dostoevsky became for her much more than a just subject of academic research. It became a life choice, the way of surviving under Soviet totalitarian regime and dominant Marxist ideology.

In his novel The Possessed (The Devils) Dostoevsky foresaw, with frightening clarity, many terrifying features of the events to come, the shadow of the future as Saraskina put it: the Russian disaster, millions of victims (he even gave the number of victimes, one hundred millions “heads” which is very close to the estimated number of the victims of communist ideology in the world ), and, what is the most important, he detected the seed of the evil ¾ the ideology of the universal happiness.

Right after the first publication of the novel and many years later, in Russia as well as abroad, The Possessed was considered as a caricature, an exaggerated, delirious vision of Dostoevsky’s paranoiac mind. Curiously enough, many Western researchers seem to echo what their Communist colleagues said about the novel: that it is reactionary. A brief look at the prefaces to American editions of The Possessed is enough in order to grasp the general attitude toward this novel and the degree of misunderstanding surrounding it:

Dostoevsky’s spite and hatred … of all imaginary ‘enemies” of Russia was perhaps entirely in harmony with his religious obsessions. In The Devils (The Possessed) he was not able to overcome them, and this is a serious blot on a novel…

Unfortunately Dostoevsky’s vision was not exaggerated. Not only did all he feared come true but there were horrors that far surpassed his imagination. That is why the Communists and Lenin especially hated the novel and banned it. That is why The Possessed became Saraskina’s life choice. This is what The Possessed should be for every Russian.

The necessity to understand the seed of evil does not exist only for Russians. The evil, which Dostoevsky prophetically detected in The Possessed, spread from Russia all over the globe, poisoned many nations, produced millions of victims and continues to exercise its influence. The devils are not dead, and this is why Saraskina’s book is so providential and important.

Ludmila Saraskina tells us about the historical, spiritual and literary experience that the novel The Possessed represents for a Russian as well as for a foreign reader. She bravely challenges established authorities and received ideas, for example Bakhtin’s ideas about time and space in Dostoevky’s work. She also shows complete disagreement with the common assumption that The Possessed is “one of the most structurally untidy of Dostoevsky’s great novel” full of “structural and artistic blemishes.”

In the second part of the book Saraskina makes an attempt to trace the activity of the heirs of Dostoevsky’s “devils” in communist Russia and in other countries. Her research is based on works of Evgenij Zamjatin, Ivan Bunin, Maximilian Voloshin, Maxim Gorkij, Andrej Belyj, George Orwell, Boris Mojaev, Robindranat Tagor and Akutagawa Runoske.

In my opinion the book is interesting and enriching not only for scholars, although they will be delighted to experience the original and talented Russian critic, but for the foreign reader, lover of Russian literature and Dostoevsky, the book will be a real discovery full of new documents, new information, new ideas and approaches. I hope that this encounter with Ludmila Saraskina and her method will be just the beginning, and that this book will awaken an interest for her criticism.

Preface of Ludmila Saraskina

I first read The Possessed, a novel that although it had been reedited after a ten year break, still had the stigma of being “reactionary” and an “ideological sabotage”, twenty years ago, when I was still a student in the Literature department. I could never imagine that I would some day write a book about it.

Like many of my contemporaries I thought that the system of “the grandiose intellectual fraud” in which our country, its people and culture, lived, was there forever. It seemed that the ideological monolith that weighed down Russian culture, somehow allowing Pushkin and Tolstoy but not trusting Dostoevsky – would remain for all time.

People say that in order not to perish, a man must find his own kind.

The novel Bessy (The Possessed) became for me, literally speaking, an ecological niche where I could live, breath freely, and feel as a human being. This book, read in an auspicious moment, built my consciousness, determined choices of my life and helped me to survive without being seduced either by the mirage of official hierarchy or by the pride of the underground.

Finally the novel guided me toward my own kind.

In this book various critical studies on The Possessed are assembled, some written a long time ago and some more recently. The “inoffensive” chapters about the poetics of the novel were conceived at the end of the seventies, the “oriental” chapters at the beginning of eighties, and the third, “political” part has come together during the last year. There are times I have felt like giving a broader artistic context to Dostoevsky’s world, going beyond the limits of the novel. This may explain chapters that exceed the limits of The Possessed itself.

The desire to understand the most debatable, the most long-suffering and, according to my deepest convictions, the most important novel of Dostoevsky, demanded many different efforts: to go into the depth of the text when lead by a line, a word, a date or a name; to go from the text toward artistic analogies and associations that were sometimes completely unexpected; and finally to go toward the text and having grown wise with the experience of the real history, to return again to its central idea.

This book certainly does not pretend to close the discussion. The real talk about The Possessed has only yet begun: the most important intellectual challenges and emotional conclusions are still ahead.

For such is the destiny of this great prophetic novel of Dostoevsky: everyone must learn its lessons starting from the zero point. To get even a half-step closer to what Dostoevsky expressed in The Possessed is an enviable lot for the reader and sometimes a real fortune.

I hope that I also have such a fortune. After the first reading of The Possessed, in the context of current issues, in other words from the position of political and social cataclysms, one should come to the understanding of The Possessed from the point of view of eternity as Dostoevsky understood it ¾ in other words from the Christian perspective.

Table of Contents:

Preface

Part I: The World of the Novel

Chapter One. In the context of the exact time (The Possessed: the fictional calendar)

Chapter Two. The history of one journey or Stavrogin in Iceland (through the pages of the chronicle)

Chapter 3 Searching for the word (Narrators in Dostoevsky’s novels)

Chapter Four. The distortion of the ideal (The character of the Lame in The Possessed)

Part II: According to Dostoevsky’s stars

Chapter One. “The Japanese Dostoevsky” Akutagawa Runoske or the overcoming of demons.

Chapter Two. The House and the World or The Possessed in India (Dostoevsky and Tagor)

Part III: The Eternal and the Temporary

Chapter One. The right of power (Thinking of the source)

Chapter Two: The shadow of “Popular revenge”

Chapter Three: The Prophecy “out of Terror”

Chapter Four: The country for the experiment

Chapter Five: The Knights of Conscience

Chapter Six. The terrible truth about the man

Chapter Seven: The image of the future

Chapter Eight: “Starting with the unlimited freedom…”

(The model of The Possessed in the novel of Mojaev Men and Women

The plan of the assigned revolution (instead of the epilogue)

from Chapter One:

The narrative function of the chronology of The Possessed corrects to a great extent a common idea about the organization of fictional time in Dostoevsky’s works. M.M. Bakhtin, who believed that the main categories of Dostoevsky’s vision are “not evolution but coexistence and interaction” and who perceived Dostoevsky’s world as unfolded “mainly in space and not in time,” denied the functional importance of the past in his characters’ lives. “His characters recall nothing, they have no biography in the sense of something in the past or something fully experienced and endured … Therefore there is no no causality in Dostoevsky’s novel, no origination, no explanations based on the past, on the influence of the environment or of upbringing, etc.” The concrete analysis of the fictional chronology of The Possessed reveals that the biographies of all the main characters of the novel must be reconstructed in a way that the distant past presents itself as a causal factor of the present and the present as a direct consequence of the past.

Conclusions of those researchers who try to apply Bakhtin’s conception to the novel The Possessed do not confirm either: “Stavrogin’s character does not have a biographical time … the information from Stavrogin’s ‘biography’ given to the reader represents only ‘moments’ and does not compose a whole and cohesive biographical time” .

The continuity of Stavrogin’s biography brought to light with each and every important life event in it (birth, study, service, marriage, travels and so on) not only exists in the novel but can be dated exactly and exemplifies the narrative importance of the chronology in Dostoevsky’s novels. On the other hand it also enlightens “temporal connections” in the novel where critical and crucial time does not exclude the chronological and sequential one as it is often suggested: “In Dostoevsky’s novels detailed chronological background (the calendar with cleary indicated boundaries between sequences) is actually fictitious. It does not influence the development of events and does not leave any traces. Chronological progression is undermined in the name of the decisive self-exposure of characters.”

To a great extent our calculations are directed in order to discern the traces that indicate the movement of the chronicle from its prehistory (the past) to the events of the present with all the complications and paradoxes this movement implies.

September 12th: the day of amazing coincidences.

Just before the beginning of the main events in the chronicle the calendar does not denote years and months anymore but rather weeks and days, and the atmosphere of expectation thickens.

The Chronicler begins the narration of the novel’s closest prehistory with a special notice: “Let me now describe the almost forgotten incident with which my story really begins. At the very end of August the Drozdovs, too, finally returned”(P 76) . Let’s verify the Chronicler’s word and take his statement “at the very end of August” literally, as the last day of the month, August 31. We can line up the chain of events from this date.

“This very day” Mrs. Stavrogin found out from Mss. Drozdov about her son’s tiff with Lisa and wrote a letter asking him to come as soon as possible. Toward the morning, in other words on the 1st of September, her project of match-making Daria and Stepan Trofimovich matured and she informed both of them on the same day. Dasha agreed immediately but Stepan Trofimovich asked for a delay until the next day. “Tomorrow,” that is on September 2, he gave his consent. The engagement was scheduled for his next birthday and the wedding two weeks after that. “A week after” (that is on September 9th) Stepan Trofimovich was in a state of confusion, and “the next day” (September 10th) he received a letter from Mrs. Stavrogin that defines the calendar dates of the events. “The day after tomorrow, Sunday, she asked Stepan Trofimovich to be at her place precisely at twelve o’clock”( P 159).

Therefore, if the calculation is correct, this particular Sunday must be September 12th. Here, our arguments obtain documentary proof. The calendar of the year 1869 clearly confirms that this supposed Sunday falls on September 12th. It is exactly on this date that the calendar of the “past” and calendar of the “present” confirm each other. Some sort of “lock” is formed: the “fatal” Sunday can only be September 12th and September 12th falls precisely on a Sunday in 1869.

The Chronicler informs us:

This Sunday when Stepan Trofimovich’s fate was to be irrevocably decided ¾ was

one of the most momentous days of my chronicle. It was a day of surprises, a day

on which events of the past came to a head and events of the future had their

beginnings, a day of harsh explanations and even greater confusion (P 159).

The fact that instead of two specially invited witnesses of the supposed engagement, there were ten uninvited guests seems to be a pure coincidence. “The completely unforeseen arrival of Nicolay Vsevolodovich (Stavrogin), who was only expected to arrive in a month’s time, was not only strange because of its unexpectedness, but because of its fateful coincidence with the present moment” (P 187), says the Chronicler about “the day of most extraordinary coincidences” (P 159).

Are these “accidents” so accidental, “surprises” so surprising, and “coincidences” so unexpected from the point of view of the chronicle’s exact calendar?

In Switzerland Nicolay Vsevolodovich promised his mother that he would come in November. On August 31 Mrs. Stavrogin implored her son “to come back at least one month earlier than he had intended” (P 79). Nevertheless, when she saw her son this September Sunday she was very surprised: “I did not expect you for another month, Nicolas!” (P 203) Therefore, Stavrogin’s early appearance is not engendered by his mother’s letter but by something else.

The fictional calendar sheds some light: on September 4th Stepan Trofimovich sent a letter to his former pupil in which he informed him about his future engagement. Nicolay Stavrogin left St. Petersburg right after he had received the news (he had just enough time) and appeared in his mother’s salon knowing the exact time and place of the gathering. Peter Verkhovensky, another “unexpected guest” also appeared there at the instigation of his father: “Leave everything and fly here to save me” (P 208). The whole gathering is not altogether as unexpected as it seems. The project imposed by Mrs. Stavrogin on her proteges is corrected by reality because it involves the interests of all those present.

The number of guests masks the truly dramatic situation which is governed, imperceptibly for others, by two of the unexpected guests: Stavrogin and Peter Stepanovich (Verkhovensky). The hidden tension of the scene resides in the fact that the accidental (yet specifically invited) visitors turn out to be its script writers, producers, and main actors.

The secret motives of Stavrogin’s arrival are to break the engagement at any price and ruin this marriage in order to keep Dasha for himself. Peter Verkhovensky’s game is, however, even more complicated and cunning. Suspecting the plot of Stavrogin, he watches his every word and gesture and, as soon as he grasps their meaning, he immediately engages in Nicolay Vsevolodovich’s party, monopolizes the conversation, and leads the scene toward the desired result. The engagement is scandalously broken, the bride is compromised, the groom is disgraced, and the hostess is cruelly hurt and insulted.

Victims and witnesses of the intrigue began to suspect that something was wrong only afterwards: “They are cunning; they had arranged it all beforehand on Sunday” (P 221).

The secret plot, however, never existed. The mainspring of Sunday’s intrigue was really known only to Peter Stepanovich: by providing a decoy for Stavrogin, a scandal which was profitable for both of them, he seems to accumulate material or blackmailing. Later Petrusha (Peter Verkhovensky) will show his cards:

I did that just because I wanted you to see what was at the back of my mind. I was playing the fool chiefly because I was trying to catch you, to compromise you.

What I really wanted to find out was how much you were afraid” (P 228).

The Chronicler narrates circumstances of the “fatal” Sunday as an average witness, “not knowing the matter: Now that it is all over and I am writing this chronicle, we know what it was all about; but at the time we did not know anything, and it is only natural that all sorts of things seemed strange to us (P 215).” The story of “the day of surprising coincidences” is like a report of a witness from the place and “from the moment” of the event.

The Chronicler will have four months, however, to think over the facts and, having the final knowledge, elucidate them from a new temporal point of view. The temporal point “then” is followed by the point “now”:

And now, having described our enigmatic situation during the eight days we knew nothing, I shall go to describe the subsequent events of my chronicle, writing, as it were, with full knowledge and describing everything as it became known afterwards and has now been explained (P 223).

The narration from “then” is mixed with the story

from “now:” “yesterday,” “today” and “tomorrow,” intersect, and the experience of the latest knowledge bares the nerve of the past moments.

Indeed, these narrative zigzags, anticipations, stops and returns to the past compose the chronicle of The Possessed ¾ this astonishing building is made of a living, multidimensional and irrevocable time.

From September 12 to October 11

The fictional time of The Possessed progresses from September 12th, thirty days from the first day of the chronicle and the arrival of the main character Nicolay Stavrogin, to the day of his death, October 11th.

Here are dates of main events in the chronicle:

¾ September 12th is “the fatal Sunday.”

¾ September 20th to 21st are the nights of Stavrogin’s visits.

¾ September 28th is the day when Peter Verkhovensky is “busy”. It is also the day in which meeting with “ours” and of the scene “Ivan the crown-prince” take place.

¾ September 29th is the search at Stepan Trofimovich’s house, Stavrogin’s visit to Tikhon, and the public confession about the marriage with Maria Lebyatkina.

¾ September 30th is the day of governesses festivities, the fire and the murder of brother and sister Lebyatkin.

¾October 1st is the day of Stepan Trofimovich’s departure, Lisa’s death, Stavrogin’s departure, and the arrival of Maria Shatova.

¾ October 2 is the birth of Maria Shatova’s child and Shatov’s murder.

¾ The night of the October 3rd is Kirilov’s suicide.

¾ October 3rd is Peter Verkhovensky’s departure and also the departure of Mrs. Stavrogin who is looking for Stepan Trofimovich.

¾ October 8th is the death of Stepan Trofimovich Verkhovensky.

¾ October 11th is Stavrogin’s suicide.

The previously enumerated days are marked by the special intensity of described events. None of the other days of this month, however, are excluded completely from the narration: some sort of event, if even only briefly mentioned, falls on each of the dates. It is even possible to find out what happened to each of the main characters on any of these days, but this information is dispersed and literally dissolved in the text. What is amazing is that if we put all these microscopic pieces together, compose individual chronologies and connect them, any particular moment belonging to a character will find its place in the combined picture of events without any slips or discrepancies.

We should not tire the reader with detailed calculations and an abundance of dates, but merely affirm that any facts fixed in time are firmly connected amongst themselves by temporal break and assembled in the general framework of chronology. All of the information concerning the days and months is as exact and reliable as the information concerning the years.

Here is an especially interesting relationship between two events. Using the previous calculations, starting with September 12th we arrive at the September 29th as the date of the search at Stepan Trofimovich’s house. Memory does not betray the Chronicler, he remembers “cold and windy, though bright September day” (P 162). The same calculation can be used to calculate the moment of Shatov’s murder, it gives us the date of October 2. We read in Kirilov’s death letter: “I, Kirilov, declare that to-day, the –th October, as about seven o’clock in the evening, I killed the student Shatov in the park… (P 617).” It can easily be proved, according to the text, that these facts (the search and the murder) are separated by no more than two days as well by two other important events: the festivities for the governesses (the day after the search) and Lisa’s death (the day after the festivities). It can be concluded that the search could only have taken place between the 28th and 30th of September and Shatov’s murder from the 1st to the 3rd of October. Therefore our calculations starting from September 12th receive sufficient confirmation. The temporal marks of “September day” and “of October” form another chronological closure.

Threads of time sewn between episodes of the novel are interwoven into a whole and complete cloth. Information about contextual moments, the numerous “two days after”, “in one day” and “next morning” that sometimes seem redundant, are actually completely necessary. The Chronicler’s narration includes the calendar that naturally contains many capricious curves of time.

It has been previously noted: “The starting point is always known. The calendar of events is extremely carefully composed and the hours are verified” . A modern researcher reasonably supposes: “Dostoevsky had an internal clock that assured a proportionality between axis of action and axis of time. This clock almost automatically corrects temporal distribution of events” .

Other questions, however, are also just: “Why does the author need so much precision and accuracy, why do the ‘explosive’ moments have to by measured by a clock that counts the hours, minutes, even seconds?” Why does the writer need an illusion of complete authenticity concerning action? It appears that the exact marks of time in Dostoevsky’s work give the opportunity to reconstruct an exact synchronized picture of events, which does not entirely reveal itself in the consecutive narration. Synchronicity is not always obvious for many events and episodes: some of them seem to be completely absent from the narration and can be reconstructed only after analyzing the context.

Since the characters of The Possessed live in a unified system of exact time, the combination of their individual chronologies may give rise to surprising semantic effects and reveal the hidden context, in other words, a complementary meaning as if it were hidden in folds of time.

It seems that the phenomena of the hidden context is an obligatory attribute of this sort of narrative system where chronology is first, exact, second, multidimensional and third, universal, as we have observed in The Possessed. Synchronicity of events, and therefore complementary meaning, does not appear if one of these attributes is missing.

from Chapter Two:

While commenting on Dostoevsky’s novel The Possessed for a foreign publisher I tried to look at it with the eyes of a foreign reader who, naturally, does not know many historical, literary, traditional and national realities of the Russian life. This new perspective organized my perception of the text in a very special way. Careful reading allowed me to notice some details that seemed unimportant but suddenly were coming to life, regaining sound. I was discovering mysteries of the author’s conception and illuminating the process of the creation of the image.

Now I would like to talk about just one, short, unnoticeable and seemingly occasional line in Dostoevsky’s novel and about the discovery toward which lead “the investigation” that this line has provoked.

The urge of wandering

After years of the dark and criminal life in St. Petersburg the main character of The Possessed, Nicolay Vsevolodovich Stavrogin, departs for the long journey abroad. There is nothing unusual in it: biographies of Russian nobility of the last century as well as biographies in Russian novels are full of descriptions of voyages and journeys. Traveling was in the spirit of times. “Crook and beg” became a voluntary or involuntary lot of many “travelers” in Russian literature. Radishev, Karamsin, Griboedov, Pushkin, Lermontov, Gogol, Herzen, Turgenev and Dostoevsky traveled frequently, either at their leisure or “by duty.” Like the authors, literary characters Tchazkij, Onegin, Petchorin, Khlestakov, Ivan Karamazinov, and other “Russian boys” “exploited the world” by running from their problems or visiting “cherished tombs,” appearing before the reader only for a short period between two journeys.

Let’s recall, however, the destinations of these voyages. The beaten path between two capitals, St. Petersburg and Moscow, became a main road of Russian literature of the 18th century. After the war of 1812 Russian travelers discovered Western Europe. Although Eugene Onegin traveled only in the limits of the Russian Empire (Moscow ¾ Nijniy Novgorod¾ Astrakhan ¾ Georgian military road ¾ Northern Caucasus ¾ Crimea ¾ Odessa ¾ St. Petersburg) and Pechorin stays in Caucasus, the Russian nobility very quickly felt at home in France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland and England that became their familiar and habitual places to stay and even live.

Exotic countries and unbeaten paths represent quite a different matter. They appear on the Russian literary map only when connected tidily with some concrete, rare and unusual event or name. For example Griboedov died in Teheran, and therefore Pechorin died on his way from Persia. There is another example. Count Fiodor Ivanovich Tolstoy (1782-1846), debaucher, gambler, duelist and, according to Lev Tolstoy, “an extraordinary, criminal and attractive personality” received, thanks to an incredible story, the nickname “the American.” In August 1803 he went on a round-the-world journey with the expedition of the admiral Krusenstern. However, because of Tolstoy’s uproarious and completely ungovernable behavior, Krusenstern left him in Kamchatka or on some Aleut island where Tolstoy lived for several months among the natives. These sort of journeys were memorized and became legends.

Let’s, however, return to the Stavrogin’s journey.

“He really visited Iceland”

Obviously Stavrogin was an unusual traveler. The geography of his journeys would bring honor to the most zealous pilgrim. Although it was quite rare to meet Russian “barin” in the East, pilgrimages to holy places were in the order of things. In any case, this part of Stavrogin’s journey can be interpreted. But Iceland? Why did Stavrogin go there, and what did he do in Iceland? It is one thing to attend lectures at German universities, or even to do a pilgrimage to Christian sacred places in Jerusalem (devotions were quite usual for European travelers). It is quite another thing is to go a far northern country in the Arctic ocean, to this mysterious Ultima Tulle, a name that means “the most removed limit of the earth in the North” as ancient historians used to call it. How should we interpret this impolite, almost disdainful remark of the Chronicler “he then joined a scientific expedition to Iceland and actually visited Iceland” (P 67) What should we think about the statement of the traveler himself: “I was even in Iceland” as if he were stressing, with this even, the unbelievable extent of his voyage? Perhaps, according to perceptions of Dostoevsky, who “sent” Stavrogin to Iceland, this island of frozen lava represented the metaphor of the end of the world, and in this regard would any other far-removed from beaten trucks geographical point do as well?

It seems that this was the attitude of the commentators of The Possessed toward Stavrogin’s Iceland. In fact, Nicolay Vsevolodovich’s mysterious journey was never commented in any edition of the novel. The line itself “and he really visited Iceland” is not a key line in the novel and looks like a simple establishment of the fact.

Yet there are never unremarkable details in Dostoevsky. The most alien of his characters live, suffer, and struggle with “eternal” existential questions in the habitual, real, and authentic world. The action of his novels takes place in very familiar interiors (lets remember the property of Fiodor Pavlovich Karmazinov which is an exact copy of Dostoevsky’s house in Staraja Russa) and on the background of easily recognizable urban landscapes, streets, yards and gateways. Even the unimportant geographical names sometimes travel from the writer’s life to pages of the novel. The fictional space of the writer is always created from familiar and real elements.

Based on the principles of Dostoevsky’s poetics we can assume that Iceland is not an unremarkable and involuntary detail in The Possessed but should be related to some sort of concrete impression of the writer and thus demands a serious commentary.

Cover letter:

Cher Monsieur Laliberté,

Veuillez recevoir ci-joints les documents suivants:

1. Mon introduction à la traduction du livre de Ludmila Saraskina

2. La table de matières

3. La préface abrégée de Ludmila Saraskina

4. Le fragment du premier chapitre

5. Le fragment du deuxième chapitre

En traduisant ce livre je commets presque un acte de folie tellement il est difficile à traduire et alourdi des innombrables citations difficiles à trouver et dispersées dans des volumes de la littérature russe et mondiale. Pourquoi je le fais quand même? Il m’a vraiment envouté et puis cette traduction représente pour moi le moyen de servir humblement mon pays en faisant connaître au lecteur occidental les découvertes faites par le chercheur russe courageux et original. Le livre est absolument excellent, c’est ma profonde conviction.

Il est aussi eclectique, c’est un ensemble d’articles qui peuvent être publiés séparemment. J’aurais même préféré de ne pas traduire la partie sur la littérature bengale par peur de ne pas trouver de citations nécessaires. Toutefois j’ai ici une amie bengale qui pourra peut-être m’aider.

Pour les citations du roman Les Possédés j’ai choisi consciemment la traduction de Magarshack. J’ai examiné d’autres traductions disponibles aux US et je trouve que celle-là est la meilleure. Je donne l’orthographe des noms propres selon Magarshack. On écrit le nom de Dostoevsky de plusieurs façons mais il me semble que l’orthographe “Dostoevsky” est maintenant généralement accepté. Le titre Les Possédés est problématique aussi car aucun mot ni anglais ni en français ne correspond tout à fait au mot russe “bess” ce qui veut dire possédé et diable en même temps. Le mot “bess” a une connotation evangélique très marquée qui est d’ailleurs soulignée par Dostoevsky lui-même. A mon avis le mot “démon” convient mieux que “diable” mais je garde le titre traditionnel. J’ai décidé d’indiquer les pages pour les citations du roman dans les paranthèses car il me paraît physiquement impossible, à cause de leur multitude, de les indiquer dans les notes en bas de la pages ou à la fin du texte. Saraskina ne les indique pas du tout ce qui ne facilite pas mon travail.

Veullez m’excuser de cette lettre informelle. Je préfère être franche. Je vous remercie de votre temps et votre intérêt pour mon projet. Si vous me répondez après le 13 mai, il faudra m’écrire à une autre adresse: herve.f.allet@vanderbilt.edu

Hervé Allet, Vanderbilt, Bât J, Rés. St. Victoire, 7 avenue Craponne,

Aix-en-Provence 13100, France

Tel: 33 4 42 93 31 89

33 4 42 38 14 79

Si vous voulez de l’information sur moi, vous pouvez consulter notre website de University of Alaska Fairbanks, Foreign Languages Department.

Mes compliments les plus distingués,

Yelena Matusevich