ShowCases: 3 Sisters, Mikado, 12th Night, Hamlet, The Importance of Being Earnest, Dangerous Liaisons, Don Juan

Summary

Others say that Athena blinded the young Tiresias by covering his eyes with her hands when he surprised her naked. Tiresias' mother, the nymph Chariclo who was dear to Athena and one of her attendants, asked the goddess to restore his sight, but Athena, not being able to do so, cleansed instead his ears in such a way that she caused him to understand the sounds of birds. Athena also gave Tiresias a staff made of cornel-wood with the help of which he could walk like those who can see.It is also said that Athena did not take the sight of young Tiresias; as the goddess explained to Chariclo, these were the old laws of Cronos, which inflicted the penalty of blindness on any mortal who beheld an immortal without consent. Since Tiresias' blindness could therefore not be taken back, Athena bestowed on him the power to utter oracles, to understand the birds (the bird-observatory of Tiresias could still be visited many generations after his death), to live a long life, and after his death, to keep his understanding among the dead.

Mikado

Questions

"Come, tell me, where have you proved yourself a seer? Why, when the Sphinx was here, did you say nothing to free the people? Yet the riddle, at least, was not for the first comer to read: there was need of a seer's help, and you were discovered not to have this art, either from birds, or known from some god. But rather I, Oedipus the ignorant, stopped her, having attained the answer through my wit alone, untaught by birds." [Oedipus to Tiresias.Sophocles, Oedipus the King 390]Notes

"The man who practices the prophet's art is a fool; for if he happens to give an adverse answer, he makes himself disliked by those for whom he takes the omens; while if he pities and deceives those who are consulting him, he wrongs the gods." [Tiresias to his daughter. Euripides, Phoenicia Women 955] The Theban seer Tiresias, son of the shepherd Everes, was given by Zeus the art of soothsaying.Still others affirm that Tiresias was once watching two snakes copulating, and when he wounded the female he was turned into a woman; but later he saw the same snakes copulating again, and having wounded the male, he was transformed into a man.

Tiresias remained a woman for seven years, and became a man again in the eighth. It is told that when Zeus and Hera once disputed whether the pleasures of love are better enjoyed by women or by men, they referred to Tiresias for a decision on account of his knowledge of both sides of love. Tiresias then told them that

"Of ten parts a man enjoys one only, but a woman enjoys the full ten parts in her heart." [Apollodorus, Library 3.6.7]

Tiresias is said to have lived an exceptionally long life. According to some, he lived for seven generations, whereas others say nine. In any case, he lived from the times of Cadmus, the founder of Thebes, to the times of the war of the EPIGONI. This war followed the one of the SEVEN AGAINST THEBES in which Oedipus' sons quarrelled for the throne when their father left Thebes, after having learnt from Tiresias that he had killed his own father and wedded her mother.

Tennyson:

TO E. FITZGERALD

OLD FITZ, who from your suburb grange,

Where once I tarried for a while,

Glance at the wheeling orb of change,

And greet it with a kindly smile;

Whom yet I see as there you sit

Beneath your sheltering garden-tree,

And watch your doves about you flit,

And plant on shoulder, hand, and knee,

Or on your head their rosy feet,

As if they knew your diet spares

Whatever moved in that full sheet

Let down to Peter at his prayers;

Who live on milk and meal and grass;

And once for ten long weeks I tried

Your table of Pythagoras,

- And seem'd at first "a thing enskied,"

As Shakespeare has it, airy-light

To float above the ways of men,

Then fell from that half-spiritual height

Chill'd, till I tasted flesh again

One night when earth was winter-b]ack,

And all the heavens flash'd in frost;

And on me, half-asleep, came back

That wholesome heat the blood had lost,

And set me climbing icy capes

And glaciers, over which there roll'd

To meet me long-arm'd vines with grapes

Of Eshcol hugeness- for the cold

Without, and warmth within me, wrought

To mould the dream; but none can say

That Lenten fare makes Lenten thought

Who reads your golden Eastern lay,

Than which I know no version done

In English more divinely well;

A planet equal to the sun

Which cast it, that large infidel

Your Omar, and your Omar drew

Full-handed plaudits from our best

In modern letters, and from two,

Old friends outvaluing all the rest,

Two voices heard on earth no more;

But we old friends are still alive,

And I am nearing seventy-four,

While you have touch'd at seventy-five,

And so I send a birthday line

Of greeting; and my son, who dipt

In some forgotten book of mine

With sallow scraps of manuscript,

And dating many a year ago,

Has hit on this, which you will take,

My Fitz, and welcome, as I know,

Less for its own than for the sake

Of one recalling gracious times,

When, in our younger London days,

You found some merit in my rhymes,

And I more pleasure in your praise.

I WISH I were as in the years of old

While yet the blessed daylight made itself

Ruddy thro' both the roofs of sight, and woke

These eyes, now dull, but then so keen to seek

The meanings ambush'd under all they saw,

The flight of birds, the flame of sacrifice,

What omens may foreshadow fate to man

And woman, and the secret of the Gods.

My son, the Gods, despite of human prayer,

Are slower to forgive than human kings.

The great God Ares burns in anger still

Against the guiltless heirs of him from Tyre

Our Cadmus, out of whom thou art, who found

Beside the springs of Dirce, smote, and still'd

Thro' all its folds the multitudinous beast

The dragon, which our trembling fathers call'd

The God's own son.

A tale, that told to me,

When but thine age, by age as winter-white

As mine is now, amazed, but made me yearn

For larger glimpses of that more than man

Which rolls the heavens, and lifts and lays the deep,

Yet loves and hates with mortal hates and loves,

And moves unseen among the ways of men.

Then, in my wanderings all the lands that lie

Subjected to the Heliconian ridge

Have heard this footstep fall, altho' my wont

Was more to scale the highest of the heights

With some strange hope to see the nearer God.

One naked peak‹the sister of the Sun

Would climb from out the dark, and linger there 30

To silver all the valleys with her shafts‹

There once, but long ago, five-fold thy term

Of years, I lay; the winds were dead for heat-

The noonday crag made the hand burn; and sick

For shadow‹not one bush was near‹I rose

Following a torrent till its myriad falls

Found silence in the hollows underneath.

There in a secret olive-glade I saw

Pallas Athene climbing from the bath

In anger; yet one glittering foot disturb'd

The lucid well; one snowy knee was prest

Against the margin flowers; a dreadful light

Came from her golden hair, her golden helm

And all her golden armor on the grass,

And from her virgin breast, and virgin eyes

Remaining fixt on mine, till mine grew dark

For ever, and I heard a voice that said

"Henceforth be blind, for thou hast seen too much,

And speak the truth that no man may believe."

Son, in the hidden world of sight that lives

Behind this darkness, I behold her still

Beyond all work of those who carve the stone

Beyond all dreams of Godlike womanhood,

Ineffable beauty, out of whom, at a glance

And as it were, perforce, upon me flash'd

The power of prophesying‹but to me

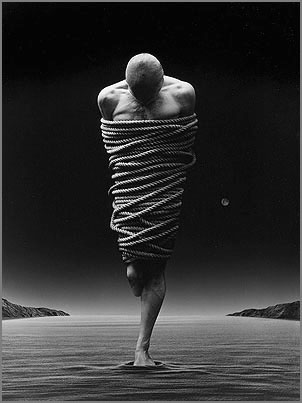

No power so chain'd and coupled with the curse

Of blindness and their unbelief who heard

And heard not, when I spake of famine, plague

Shrine-shattering earthquake, fire, flood, thunderbolt,

And angers of the Gods for evil done

And expiation lack'd‹no power on Fate

Theirs, or mine own! for when the crowd would roar

For blood, for war, whose issue was their doom,

To cast wise words among the multitude

Was fiinging fruit to lions; nor, in hours

Of civil outbreak, when I knew the twain

Would each waste each, and bring on both the yoke

Of stronger states, was mine the voice to curb

The madness of our cities and their kings.

Who ever turn'd upon his heel to hear

My warning that the tyranny of one

Was prelude to the tyranny of all?

My counsel that the tyranny of all

Led backward to the tyranny of one?

This power hath work'd no good to aught that lives

And these blind hands were useless in their wars.

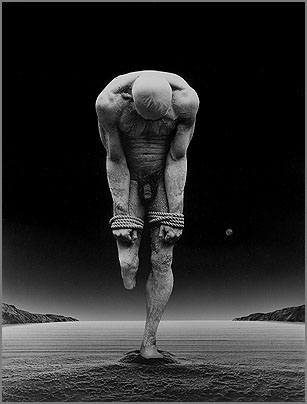

O. therefore, that the unfulfill'd desire,

The grief for ever born from griefs to be

The boundless yearning of the prophet's heart‹

Could that stand forth, and like a statue, rear'd

To some great citizen, wim all praise from all

Who past it, saying, "That was he!"

In vain!

Virtue must shape itself im deed, and those

Whom weakness or necessity have cramp'd

Withm themselves, immerging, each, his urn

In his own well, draws solace as he may.

Menceceus, thou hast eyes, and I can hear

Too plainly what full tides of onset sap

Our seven high gates, and what a weight of war

Rides on those ringing axlesl jingle of bits,

Shouts, arrows, tramp of the horn-footed horse

That grind the glebe to powder! Stony showers

Of that ear-stunning hail of Ares crash

Along the sounding walls. Above, below

Shock after shock, the song-built towers and gates

Reel, bruised and butted with the shuddering

War-thunder of iron rams; and from within

The city comes a murmur void of joy,

Lest she be taken captive‹maidens, wives,

And mothers with their babblers of the dawn,

And oldest age in shadow from the night,

Falling about their shrines before their Gods,

And wailing, "Save us."

And they wail to thee!

These eyeless eyes, that cannot see thine own,

See this, that only in thy virtue lies

The saving of our Thebes; for, yesternight,

To me, the great God Ares, whose one bliss

Is war and human sacrifice‹himself

Blood-red from battle, spear and helmet tipt

With stormy light as on a mast at sea,

Stood out before a darkness, crying, "Thebes,

Thy Thebes shall fall and perish, for I loathe

The seed of Cadmus‹yet if one of these

By his own hand‹if one of these‹"

My son, No sound is breathed so potent to coerce,

And to conciliate, as their names who dare

For that sweet mother land which gave them birth

Nobly to do, nobly to die. Their names,

Graven on memorial columns, are a song

Heard in the future; few, but more than wall

And rampart, their examples reach a hand

Far thro' all years, and everywhere they meet

And kindle generous purpose, and the strength

To mould it into action pure as theirs.

Fairer thy fate than mine, if life's best end

Be to end well! and thou refusing this,

Unvenerable will thy memory be

While men shall move the lips; but if thou dare‹

Thou, one of these, the race of Cadmus‹then

No stone is fitted in yon marble girth

Whose echo shall not tongue thy glorious doom,

Nor in this pavement but shall ring thy name

To every hoof that clangs it, and the springs

Of Dirce laving yonder battle-plain,

Heard from the roofs by night, will murmur thee

To thine own Thebes, while Thebes thro' thee shall stand

Firm-based with all her Gods.

The Dragon's cave

Half hid, they tell me, now in flowing vines‹

Where once he dwelt and whence he roll'd himself

At dead of night‹thou knowest, and that smooth rock

Before it, altar-fashion'd, where of late

The woman-breasted Sphinx, with wings drawn back

Folded her lion paws, and look'd to Thebes.

There blanch the bones of whom she slew, and these

Mixt with her own, because the fierce beast found

A wiser than herself, and dash'd herself

Dead in her rage; but thou art wise enough

Tho' young, to love thy wiser, blunt the curse

Of Pallas, bear, and tho' I speak the truth

Believe I speak it, let thine own hand strike

Thy youthful pulses into rest and quench

The red God's anger, fearing not to plunge

Thy torch of life in darkness, rather thou

Rejoicing that the sun, the moon, the stars

Send no such light upon the ways of men

As one great deed.

Thither, my son, and there

Thou, that hast never known the embrace of love

Offer thy maiden life.

This useless hand!

I felt one warm tear fall upon it. Gone!

He will achieve his greatness.

But for me I would that I were gather'd to my rest,

And mingled with the famous kings of old

On whom about their ocean-islets flash

The faces of the Gods‹the wise man's word

Here trampled by the populace underfoot

There crown'd with worship and these eyes will find

The men I knew, and watch the chariot whirl

About the goal again, and hunters race

The shadowy lion, and the warrior-kings

In height and prowess more than human, strive

Again for glory, while the golden lyre

Is ever sounding in heroic ears

Heroic hymns, and every way the vales

Wind, clouded with the grateful incense-fume

Of those who mix all odor to the Gods

On one far height in one far-shining fire.

----------

"One height and one far-shining fire!"

And while I fancied that my friend

For this brief idyll would require

A less diffuse and opulent end,

And would defend his judgment well,

If I should deem it over nice‹

The tolling of his funeral bell

Broke on my Pagan Paradise,

And mixt the dream of classic times,

And all the phantoms of the dream,

With present grief, and made the rhymes,

That miss'd his living welcome, seem

Like would-be guests an hour too late,

Who down the highway moving on

With easy laughter find the gate

Is bolted, and the master gone.

Gone onto darkness, that full light

Of friendship! past, in sleep, away

By night, into the deeper night!

The deeper night? A clearer day

Than our poor twilight dawn on earth‹

If night, what barren toil to be!

What life, so maim'd by night, were worth

Our living out? Not mine to me

Remembering all the golden hours

Now silent, and so many dead,

And him the last; and laying flowers,

This wreath, above his honor'd head,

And praying that, when I from hence

Shall fade with him into the unknown,

My close of earth's experience

May prove as peaceful as his own.